Other Hormonal Conditions

Disorders affecting the adrenal gland

Adrenal glands, which are also called suprarenal glands, are small, triangular glands located on top of both kidneys. An adrenal gland is made of two parts: the outer region, called the adrenal cortex, and the inner region, called the adrenal medulla. The adrenal glands work interactively with the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, as well as secrete hormones that affect metabolism, blood chemicals, and certain body characteristics. Adrenal glands also secrete hormones that help a person cope with both physical and emotional stress.

Hormones secreted by the adrenal glands include the following:

- Adrenal cortex

- Corticosteroid hormones (hydrocortisone or cortisol) – to help control the body’s use of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, suppress inflammatory reactions in the body, and affect the immune system function.

- Aldosterone – inhibits the level of sodium excreted into the urine, and maintains blood potassium levels, blood volume and blood pressure.

- Androgenic steroids (androgen hormones) – hormones that have an effect on the development of some types of hair growth, acne, and male characteristics.

- Adrenal medulla

- Epinephrine (adrenaline) – increases the heart rate and force of heart contractions, facilitates blood flow to the muscles and brain, causes relaxation of smooth muscles, helps with conversion of glycogen to glucose in the liver, and other activities.

- Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) – this hormone has little effect on smooth muscle, metabolic processes, and cardiac output, but has strong vasoconstrictive effects (narrowing of the blood vessels), thus, increasing blood pressure.

If the adrenal glands cannot produce enough cortisol the hypothalamus detects the low blood levels of cortisol. The hypothalamus, in turn, stimulates the pituitary gland to make ACTH in order to stimulate the adrenal glands.

In some cases, the ACTH stimulation causes the glands to grow. If there is a defect in the production of cortisol due to deficiency of an enzyme (usually 21-hydroxylase), overstimulation of the adrenal glands can also lead to overproduction of androgens, which can lead to masculinization. This situation occurs in patients with a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia or CAH. Some patients with CAH are unable to make aldosterone. Treatment includes replacement of cortisol with cortisosteroid medication. This reduces the ACTH-stimulation of the gland and in turn, the androgen production is reduced. Some patients also require treatment with fludrocortisone if they cannot make aldosterone.

Credit goes to: https://childrenswi.org/medical-care/endocrine/endocrine-conditions/disorders-affecting-the-adrenal-gland

What Does “Ambiguous Genitalia” Mean?

Sex organs develop with three basic steps. If something goes wrong with this process, a sexual development disorder (DSD) can happen. DSDs are caused by hormones. Genitals can develop in ways that aren’t normal looking. They can be unclear or “ambiguous.” A baby can have features from both genders. The medical term “intersex” is also used to describe ambiguous genitals.

The sex of a baby can be tested to help parents raise a child. Surgery can be used to help clarify a baby’s gender.

Please note: DSD’s are not the same as transsexualism. A transsexual is a person who doesn’t see themselves as their defined gender. DSD’s are different. They are caused by hormones that change the way a fetus develops.

How Do Genitalia Normally Form?

Sex organs develop with three basic steps:

- The genetic sex is set when the sperm fertilizes the egg. An XX pair of chromosomes means that the baby is female. An XY pair means that the baby is male.

- Next, gonads (sex glands) form into either testis for a boy or ovaries for a girl.

- Then, the inner reproductive system, and outer genitals develop. Hormones from either the testis or ovaries shape the outer genitals.

At conception, the mother shares an X chromosome and the father an X or Y chromosome. The pair creates either a female embryo (XX), or a male embryo (XY). At this point, the male and female embryos look the same.

Embryos start with two gonads. They can become either testes or ovaries. Each embryo also starts with both male and female inner genital structures. They become male OR female reproductive structures.

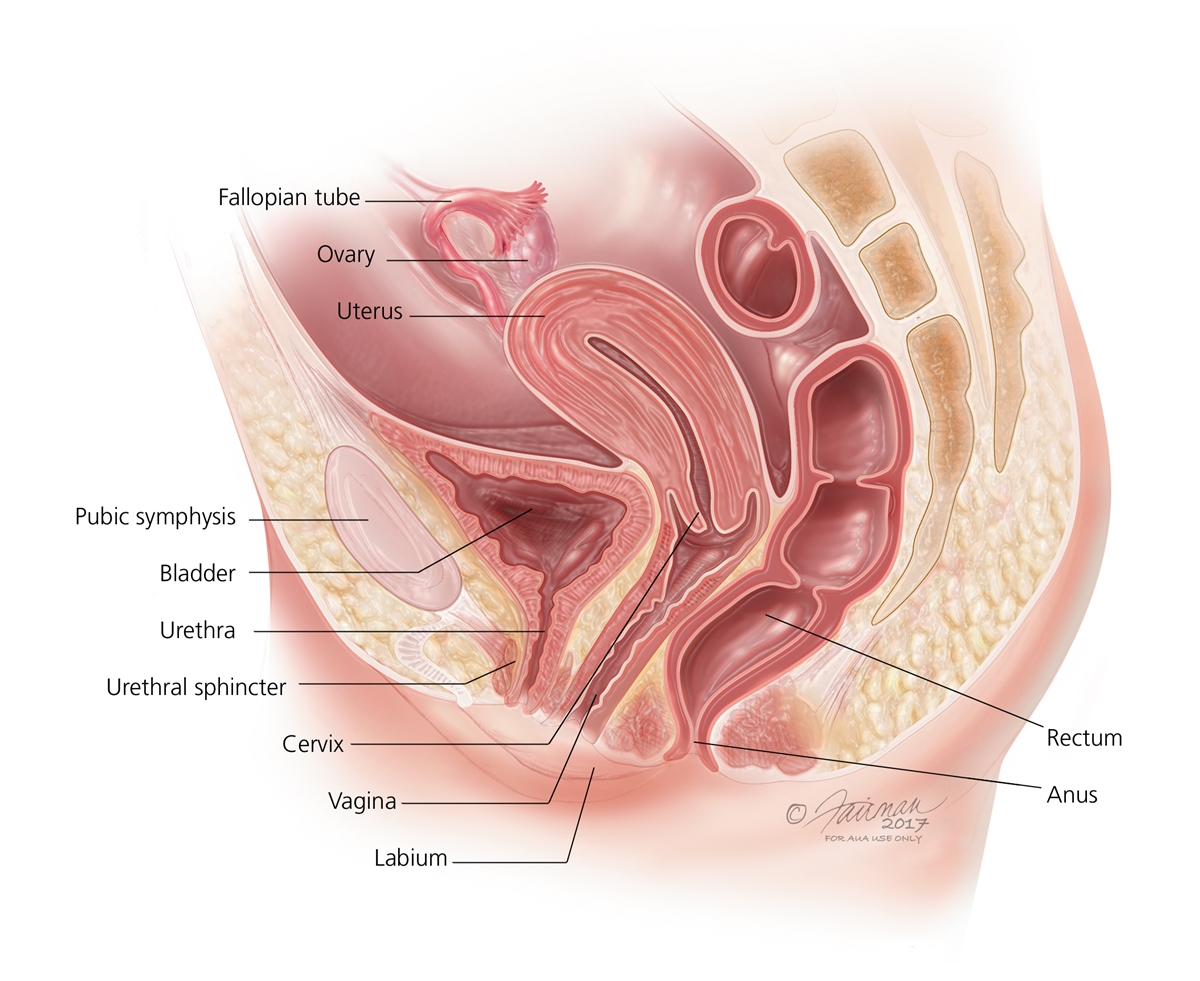

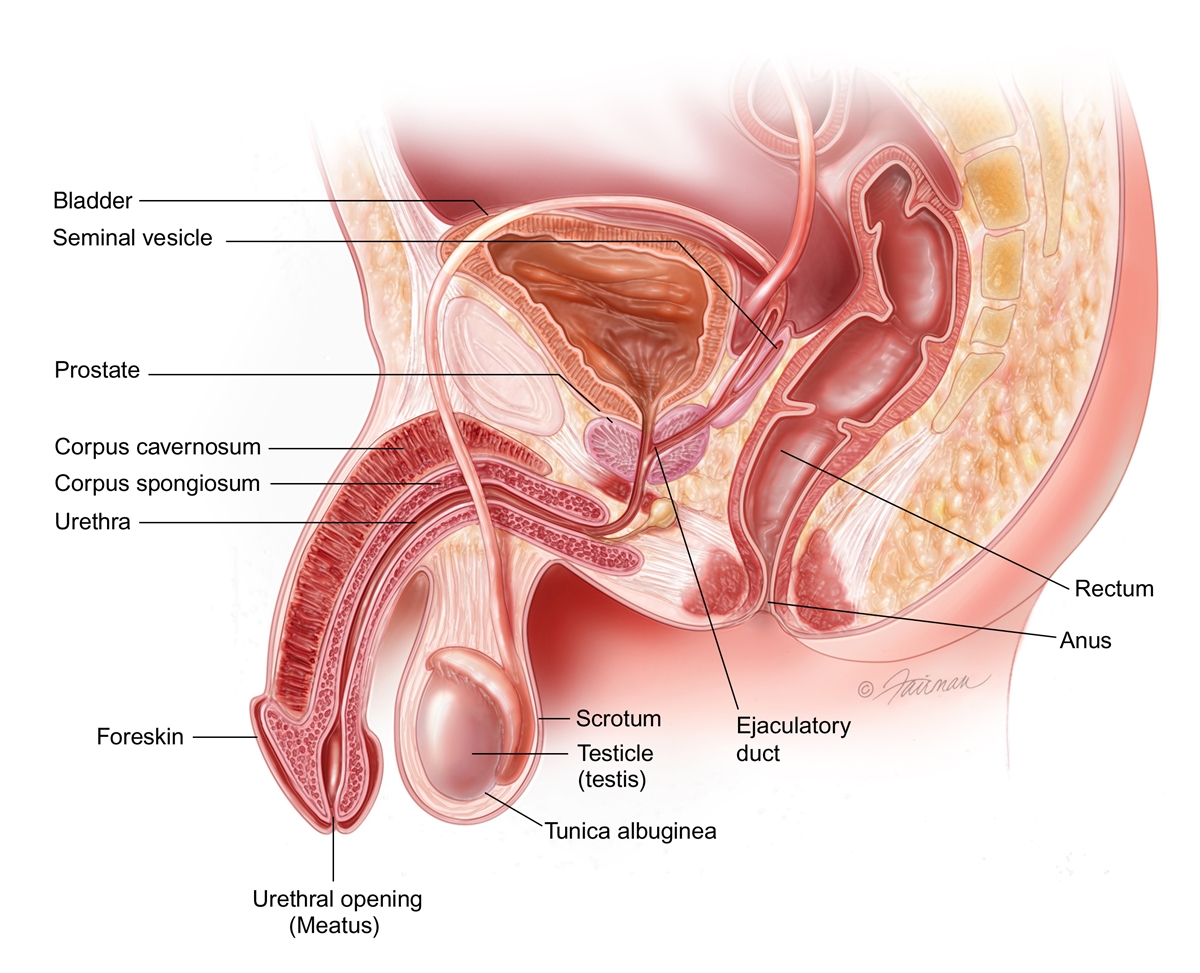

For girls, very little change is needed for the vagina to look normal. The vagina forms right away, before the ovaries have fully formed. For boys, a series of steps must take place. This starts with the growth of testes. The cells of the testes must begin to make testosterone, the male hormone. Then a more powerful hormone (dihydrotestosterone or DHT) causes genital tissues to change. It forms the slit-like groove of the urethra. Then the penis, which was first the size of a clitoris, becomes larger. The tissue on either side forms into the scrotum. Later, the testes move down into the scrotum. At the same time, structures known as mullerian ducts form inner organs. They either become fallopian tubes and a uterus (in a girl), or disappear (in a boy).

All of these steps take place during the first three months of pregnancy. After that, the outer sex organs look like either a penis or vagina.

DSDs can be passed down from a parent, or have no clear cause.

Diagram of the Female Reproductive System

Enlarge

Diagram of the Male Reproductive System

Enlarge

DSDs can cause a range of problems. Some of the signs include:

- Sex organs that don’t look male or female

- Menstruation can begin at an odd age

- Hormonal or electrolyte imbalances

- Hypospadias can form. This is where the penis opening is not at the tip, and the testes have not dropped

46XX DSD

With 46XX, the inner organs are female (the ovaries are normal) but the vagina looks masculinized. This is caused by too many male hormones. Some causes are:

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia: A common DSD. Too many male hormones cause a girl’s external sex organs to become too large. The clitoris can grow to look like a penis. Another issue is the vaginal opening may not be visible. Hormone and enzyme levels are off-balance. The body’s level of cortisol may be far too low.

- Placental aromatase deficiency: This is from a rare enzyme problem in the placenta. It causes the fetus to get too much testosterone.

- Hormonal medications: Sometimes pregnant mothers are given hormones during pregnancy. They can masculinize the fetus.

- Maternal hormonal imbalance: A pregnant mother can, herself, have a hormone imbalance. This may give the fetus too much testosterone.

46XY DSD

With 46XY, the gonads become testes, but the appearance of the penis is unclear. The cause may be from:

- Testosterone biosynthesis defect: One of the testis’ five enzymes that usually build testosterone, is missing or low.

- 5a-reductase deficiency: There is a low level of the 5a-reductase enzyme. This enzyme is found in male gonads. Without it, testosterone can’t create enough DHT to make male sex organs.

- Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome: In this problem, the cells of the body are only a little responsive to testosterone.

- Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: In this problem, the body’s cells are not responsive to testosterone. The outer genitalia look female.

Disorders of Gonadal Differentiation

In these cases the gonads may not fully develop into testes. There are three types:

- Mixed gonadal dysgenesis: In this case, one gonad stays premature. The other has formed a testis.

- Partial gonadal dysgenesis: The gonads formed some testicular tissue, but not fully. The testes can’t work properly.

- Gonadal dysgenesis: In this case, both gonads stay premature. They do not become testes.

Ovotesticular DSD

In this rare case, the gonads have both ovarian and testicular tissue. Sometimes there is an ovary on one side and a testis on the other.

Many times it’s clear to see when there’s a gender problem. In other cases, it’s not so simple. Most children are diagnosed at birth. Sometimes a DSD is not found until the teen years.

To make a proper diagnosis, and define a child’s gender, there are tests.

These include:

- A physical exam of outer sex organs

- Blood tests to show your child’s chromosomes and hormone levels

- Ultrasound or MRI tests to see the internal organs

- A genitogram to view inner sex organs. This includes X-rays and catheterization of the openings between the genitals and anus. This will show the urethra and the size of a vagina, if present. This test is helpful for planning surgery.

- Dye may be used

- A biopsy, to test the gonad tissue under a microscope

- In rare cases, gene probe studies may help

- For example, studies of the chromosomes with karyotyping will help define a 44XY DSD

Often, very high or low hormone levels are found in the blood. This tells your doctor the cause of the DSD. Once recognized, hormone levels can often be corrected.

A clear diagnosis will help define sexual function and fertility. Also, it will help parents know what to expect at puberty. All of this helps when defining the baby’s gender and finding treatment.

The first step is to understand the child’s gender. The next step is to consider treatment and support for the child’s emotional well-being.

Treatment depends on what caused the problem. Treatment often involves reconstructive surgery. This would remove or create appropriate sex organs. Surgeons with experience can offer very normal looking results. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is also often part of the treatment plan.

For girls with mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia, surgery may not be needed. Hormone therapy may be all that she needs. When the imbalance is managed, she can live a normal life. If the vagina is blocked, surgery would help. This is often done within the first 12-18 months of life.

With vaginal surgery, care is taken to protect clitoral sensitivity. The goal is to prevent injury to the sensory nerves and blood supply. Often, a new opening with vaginal surgery is thin. More surgery may be needed as the child grows. Or, exercises to “stretch” the opening may be done before sexual activity begins.

Surgery for boys with severe hypospadias is often successful. It forms a longer, free penis that can look normal. Any separation of the scrotal sacs would be repaired at the same time. Surgery is done in one or two stages between 6 and 18 months of age. Once healed, the penis grows in pace with normal physical growth. Surgery doesn’t harm a boy’s ability to feel sensation or have an erection.

All credit goes to https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/a_/ambiguous-(uncertain)-genitalia

Hypoglycemia in Children

What is hypoglycemia in children?

Hypoglycemia is when the level of sugar (glucose) in the blood is too low. Glucose is the main source of fuel for the brain and the body. The normal range of blood glucose is about 70 to 140 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). The amount differs based on the most recent meal and other things, including medicines taken. Babies and small children with type 1 diabetes will have different goal ranges of blood glucose levels than older children.

What causes hypoglycemia in a child?

Hypoglycemia can be a condition by itself. Or it can be a complication of diabetes or other disorder. It’s most often a problem in someone with diabetes. It occurs when there’s too much insulin. This is also called an insulin reaction.

Causes in children with diabetes may include:

Too much insulin or oral diabetes medicine

The wrong kind of insulin

Incorrect blood-glucose readings

A missed meal

A delayed meal

Not enough food eaten for the amount of insulin taken

More exercise than usual

Diarrhea or vomiting

Injury, illness, infection, or emotional stress

Other health problems, such as celiac disease or an adrenal problem

Taking diabetes medicine called sulfonylurea

Problems present at birth (congenital) with how the body processes glucose and starches

Rare genetic disorders

Hypoglycemia may also occur in these cases:

After strenuous exercise

During period of time not eating food (fasting)

When taking certain medicines

After abusing alcohol or salicylates such as aspirin

Conditions that cause too much insulin in the body (hyperinsulinism)

Tumor on the pancreas that makes insulin (insulinoma)

Which children are at risk for hypoglycemia?

The biggest risk factor is having type 1 diabetes.

What are the symptoms of hypoglycemia in a child?

Symptoms can occur a bit differently in each child. They can include:

Shakiness

Dizziness

Sweating

Hunger

Headache

Irritability

Pale skin

Sudden moodiness or behavior changes, such as crying for no reason or throwing a tantrum

Clumsy or jerky movements

Trouble paying attention

Confusion

Tingling feelings around the mouth

Seizure

Nightmares and confusion on awakening

The symptoms of hypoglycemia can be like other health conditions. Make sure your child sees his or her healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

How is hypoglycemia diagnosed in a child?

The healthcare provider will ask about your child’s symptoms and health history. He or she may also ask about your family’s health history. He or she will give your child a physical exam. Your child may also have blood tests to check blood sugar levels.

When a child with diabetes has symptoms of hypoglycemia, the cause is most often an insulin reaction.

For children with symptoms of hypoglycemia who don’t have diabetes, the healthcare provider may:

Measure levels of blood sugar and different hormones while the child has symptoms

See if symptoms are relieved when the child eats food or sugar

Do tests to measure insulin action

Your child may need to do a supervised fasting study in the hospital. This lets healthcare providers test for hypoglycemia safely.

How is hypoglycemia treated in a child?

Treatment will depend on your child’s symptoms, age, and general health. It will also depend on how severe the condition is.

For children with diabetes, the goal of treatment is to maintain a safe blood glucose level. This is done by:

Testing blood glucose often

Learning to recognize symptoms

Treating the condition quickly

To treat low blood glucose quickly, your child should eat or drink something with sugar such as:

Orange juice

Cake icing

A hard candy

Don’t use carbohydrate foods high in protein such as milk or nuts. They may increase the insulin response to dietary carbohydrates.

Blood glucose levels should be checked every 15 to 20 minutes until they are above 100 dg/dL.

If hypoglycemia is severe, your child may need a glucagon injection. Talk with your child’s healthcare team about this treatment.

What are possible complications of hypoglycemia in a child?

The brain needs blood glucose to function. Not enough glucose can impair the brain’s ability to function. Severe or long-lasting hypoglycemia may cause seizures and serious brain injury.

What can I do to prevent hypoglycemia in my child?

Not all episodes of hypoglycemia can be prevented. Most children with type 1 diabetes will have hypoglycemia. The chances of severe hypoglycemia go down as your child gets older. But you can help prevent severe episodes by:

Testing your child’s blood glucose often, including at night

Checking that the glucose test strips are not outdated and match the glucose meter

Recognizing symptoms

Treating the condition quickly

Other ways to minimize or prevent hypoglycemia include making sure your child:

Takes medicines at the right time

Eats enough food

Doesn’t skipping meals

Checks blood glucose before exercising

Eats a healthy snack if needed. The snack should include complex carbohydrates and some fat, if possible.

How can I help my child live with hypoglycemia?

Children with type 1 diabetes or other conditions that may cause hypoglycemia need to follow their care plan. It’s important to test blood glucose often, recognize symptoms, and treat the condition quickly. It’s also important to take medicines and eat meals on a regular schedule.

Work with your child’s healthcare provider to create a plan that fits your child’s schedule and activities. Teach your child about diabetes. Encourage them to write down questions they have about diabetes and bring them to healthcare provider appointments. Give them time to ask the provider the questions. Check that the answers are given in a way your child can understand. Work closely with school nurses, teachers, and psychologists to develop a plan that’s right for your child.

When should I call my child’s healthcare provider?

Call your child’s healthcare provider if your child:

Has hypoglycemia often

Has moderate to severe episodes of hyperglycemia

Key points about hypoglycemia in children

Hypoglycemia occurs when the blood glucose is too low to fuel the brain and the body.

It may be a condition by itself, or may be a complication of diabetes or another disorder.

To treat low blood glucose right away, your child should eat or drink something with sugar, such as orange juice, milk, cake icing, or a hard candy. They should follow with food with complex carbohydrates, fat, and protein, such as a peanut butter sandwich on whole-grain bread.

Severe or long-lasting hypoglycemia may result in seizures and serious brain injury.

All credit goes to https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=hypoglycemia-in-children-90-P01960